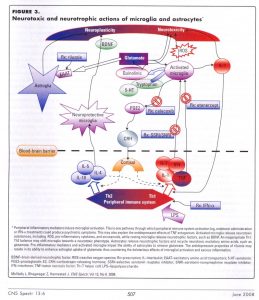

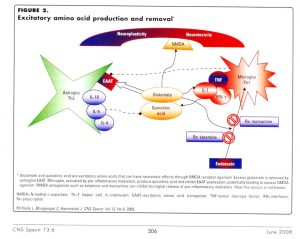

Many people intuitively understand that increased stress, either in the form of an acute trauma or more chronic stress, can contribute to or precipitate an episode of depression. Often, though, people think that they need to snap themselves out of it, just get through the stress and things will be fine. An appreciation of what stress does in the body and to the brain in particular goes a long way toward helping people understand the mechanisms behind it. Commonly, a depressive episode will occur in someone who already has a predisposition to depression. A family history of depression and/or past episodes of depression certainly increase one’s risk to become depressed. What may not be as widely understood is that stress causes inflammation in the body. Indeed, the immune system responds to stress by releasing chemicals known as cytokines (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3741070/), which can enter the brain by crossing the blood-brain barrier (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blood%E2%80%93brain_barrier). Cytokines involved include interferons, interleukins and tumor necrosis factor. These substances, which play a vital role in the function of a healthy immune system, can also activate specialized cells in the brain known as microglia. Microglia are located throughout the brain and spinal cord and account up to 15% of all cells found within the brain. They function as immune cells in the brain and are the first and main form of active immune defense in the central nervous system (CNS). When there is inflammation and these cells are activated, they release toxic substances that help to transmit the inflammation happening outside the brain to inside the brain. When that happens, these cells also begin to siphon niacin, a B vitamin that plays a role in cellular energy production, and tryptophan, the amino acid necessary to produce serotonin, which is thought to help regulate sleep, appetite and mood. (https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002332.htm) Instead of serotonin production, though, a different pathway is activated and the end result is an increased production of glutamate. Glutamate is one of the two main excitatory neurotransmitters in the brain, and therefore is essential for many of the bodies natural processes. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10807/) However, in excessive amounts, as often found either in chronic states of inflammation or after a closed head injury, it is toxic to brain cells and leads to cell death. Depleting the brain of the building block for serotonin can increase vulnerability to depression. Another consequence is the activation of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a principal mediator of inflammation in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. When PGE2 increases in the brain, the hypothalamus gland (https://www.endocrineweb.com/endocrinology/overview-hypothalamus) releases a hormone that then signals the pituitary gland (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMHT0022786/) to release another hormone that tells the adrenal glands (https://www.endocrineweb.com/endocrinology/overview-adrenal-glands) to begin releasing cortisol. Cortisol (http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/stress/art-20046037) is a steroid hormone that is often elevated during times of stress and when chronically elevated has been implicated in the development of depression as well as a host of other illnesses. Antidepressant medications, such as SSRI’s (Prozac is the prototype for this class) and SNRI’s (Effexor is the prototype for this class) can actually interfere with the entry into the brain of pro-inflammatory immune chemicals, so in addition to boosting brain levels of serotonin and/or norepinephrine, these medications may have an anti-inflammatory effect in the brain as well and therefore be neuroprotective. This narrative is shown graphically below:

We live in a world where general stress levels are increasing. Stress is a generic term, and it manifests in multiple ways. It can be the stress of chronic childhood trauma, such as sexual abuse. It a can be poor nutrition, poverty, limited access to good health care and living in polluted or overcrowded areas. It can be in the form of dealing with multiple losses, job stress, relationship stress or stress about the current political climate. The list is nearly endless. And certainly, one’s response to stress is often key. Some individuals seem to be more stress hardy, while other people seem to fall apart with the slightest of provocation. So how can we become more effective at managing stress when it is ever increasing? How can we adopt an anti-inflammatory approach to living our lives? Short of a radical departure from certain lifestyles, it seems inescapable, though I suspect that pursuing the fantasy of a much simpler lifestyle for many would bring about stresses of its own.

Let’s start with food. What we eat has become a large source of inflammation in our bodies. Processed food, fast food, food with a lot of added sugar and not the proper kind of fat, frequent consumption of grilled or charred-broiled food – all trigger inflammatory responses in the body. Chronic inflammation ultimately leads to illness, including an increased risk for depression. Changing one’s diet to eat more regularly at the lower end of the food chain, eating organic foods whenever possible (more recently this has become increasingly important with respect to wheat products (http://realfarmacy.com/reason-toxic-wheat/), and trying to avoid sugary and processed foods can be vitally important to lowering the overall burden of inflammation in the body and thereby leading to a healthier brain as well. According to Mark Hyman, MD, author of The Pegan Diet (https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/53915359-the-pegan-diet), food is information. People need to consider what information they are providing with the food they choose to eat.

Another important piece to diet is the impact food has on the microbiome. If the microbiome becomes imbalanced or unhealthy (dysbiosis), that can trigger the immune system to release cytokines, thereby raising inflammation levels in the body. Someone who has to take an antibiotic has most likely experienced the consequences of an unhappy microbiome, with the resulting diarrhea, abdominal cramping and other GI symptoms. If food is information, we need to consider how our microbiome is going to respond to it. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7589951/) Sometimes a good probiotic supplement can help. Readers should consult their doctors before taking anything.

Exercise is another way not only to stay in shape but also to reduce inflammation in the body. Practices such as meditation, Qi Gong, Tai Chi and martial arts can have an anti-inflammatory effect as can regular sexual activity and trying to maintain a balance between work and play. Psychotherapy and the possible use of psychotropic medication can also play a role in reducing inflammation in the body.

Sleep is also vitally important to overall health and in particular the prevention of inflammation. It’s well known that chronically disrupted or fragmented sleep leads to increased risks for cardiovascular disease (heart attack, stroke, high blood pressure), pulmonary hypertension (in untreated sleep apnea), diabetes, obesity, dementia and premature death. Sleep loss alters the mediators of inflammation (cytokines) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3548567/), which contributes to the cascade of inflammatory chemicals in the brain as outlined earlier. Trying to maintain sleep hygiene, which means no screen time at night, avoiding caffeine (or making sure you consume none past noon), avoiding other stimulating activity at night, and sleeping in a dark and quiet room can go a long way to help establish healthier sleep rhythms.

Fighting inflammation in an increasingly stressed world is a complicated challenge to meet. With so many variables and so many choices, anyone can become easily overwhelmed and that can lead to inertia and hopelessness with a default to a person’s usual routines and habits. Pick one thing at a time to change and get comfortable with that before moving forward. Finding ways to stay grounded in one’s day each day can provide the anchor needed to maintain momentum and with it, the incentive to continue to change.